Hamilton

해밀턴

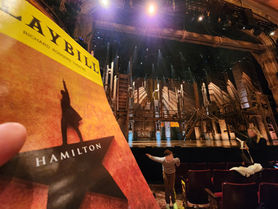

Hamilton pulsed with breath and rhythm. Dense lyrics flowed with clarity; history felt urgent, alive. Offbeat delivery made Hamilton thrilling, Jefferson disarmed with charm, and King George raged like a royal madman. It was more than brilliance—it was truth on fire. And in that fire, a spark: hope for a Korean licensed run.

REVIEW

I saw Hamilton as part of a whirlwind trip — six shows in five days — and though I knew it would be tightly constructed and brilliantly written, I didn’t expect to be so deeply moved. Hamilton isn’t just history set to music; it’s a rhythm-driven emotional machine. I had listened to the original cast recording and admired the lyrical construction, but watching it live made me feel the stakes, the tension, and the physicality of every line.

The show opens with the entire company’s intro, followed by Aaron Burr (Marc delaCruz), who stands alone under a spotlight and sings, “I’m the damn fool that shot him,” casting a long shadow over everything that follows. It’s a narrative masterstroke: consequence before cause, regret before ambition. And yet, we laugh throughout the show. We laugh at Burr and Hamilton debating like MCs in a rap battle. We laugh when Jefferson bursts in, full of swagger. We even laugh when Hamilton’s son Philip says with a grin, “Everything is legal in New Jersey.” But that moment is followed by his death in a duel. Miranda never hides the tragedy — he lets it sneak up on us through rhythm and humor, making the emotional impact even stronger.

Hamilton, Trey Curtis, played with intelligence and bite, often shifted beats ever so slightly. In a musical as tightly choreographed and rhythmically packed as this, even small variations gave the show freshness. Burr was a revelation. His rap delivery was flawless — fluid and exacting. It quietly shattered my own preconceptions. I would never have guessed his Asian heritage if I hadn’t looked him up afterward.

George Washington, performed by a younger-looking alternate, J. Quinton Johnson, carried gravitas through vocal depth and pacing. John Laurens, Jacob Guzman, who returns in Act II as Philip Hamilton, brought sincerity and vulnerability. Thomas Jefferson, Bryson Bruce, stole every scene with flair and timing, while James Madison, Ebrin R. Stanley, anchored their scenes with rhythm and weight.

The Schuyler sisters offered three very different energies. Angelica, Stephanie Umoh, sang with power and control, even as she portrayed restraint. Eliza, Morgan Anita Wood, had a gentle voice, but I found myself leaning in to catch her diction, perhaps because she moved her mouth very little. Peggy, Cherry Torres, who returns as Maria Reynolds, showed vocal strength in her brief but pivotal appearance.

And then there was the ensemble. One silent figure — known as "The Bullet" — moved through the show, building presence without a line of text. She handed Hamilton the gun in the final duel. Her choreography became a symbol of fate, and she was unforgettable.

Thomas Kail’s staging was minimalist but alive. Light brown wood, ropes, a second level, and a rotating stage — yet it felt full. Just as I had felt with Sweeney Todd across the street, the economy of physical objects gave more room for bodies to carry the story. The ensemble became the landscape: city, battlefield, crowd, conscience.

King George III, Thayne Jasperson, was pure comedic brilliance. I had seen so many clips of Jonathan Groff that I worried no one else could match him — but this actor did. He entered stiff with delusion, enunciated every syllable like a royal decree, and received thunderous applause each time.

I couldn’t return to the show due to my schedule, and that became my biggest regret. One performance wasn’t enough.

Could Hamilton Come to Korea?

Before I saw the show, I thought it couldn’t be done. The lyrics are too dense, too embedded in American idioms. But while watching, I changed my mind. Korean rappers are just as fast — if not faster — and Korea has the linguistic agility to meet this material head-on. The issue is not speed, but spirit: to recreate the truth of Hamilton in Korean would require a complete reimagining, not a direct translation.

It would be costly — far more so than other licensed translations. And Miranda’s approval would likely involve a long back-and-forth process, given how tightly he controls the work. That may be intimidating for any production company.

But if Lin-Manuel Miranda wrote Hamilton alone, I believe it can be adapted with care by a Korean lyricist who understands both hip-hop and history — and, most importantly, by working closely with the actors. Rap must be lived to be delivered. If a line doesn’t sit right, they’ll feel it. A Korean version must be rehearsed into rhythm, not imposed from above.

Korea has staged many musicals based on European history, often playing freely with fact and fiction. But Hamilton must be treated differently. No invented subplots, no distortion of the ideological core. The story is too rooted in actual agony — the building of a nation and the cost of personal pride. What it needs is rewording, not rewriting.

When I visited Italy, my taxi driver was listening to hip-hop. At a Coldplay concert in Rome, I watched thousands chant in English with no need for subtitles. Rap and music are already global. Korean audiences, no strangers to rhythm or revolution, would understand Hamilton deeply.

It’s not a lack of talent that keeps Hamilton from Korea. It’s the shame of being unknown. There are artists here who could meet Miranda’s material head-on — and give it new life. The world just hasn’t heard them yet.

And if one day it does — if Hamilton is reimagined for a Korean stage, performed in Korean but without a drop of distortion — then I’ll be there, watching again. More than once.

All photos in this gallery were taken personally when photography was allowed, or are of programs, tickets, and souvenirs in my collection.